As her feet pounded the dirt road — mile after mile — through the Sahara Desert in northern Africa, the wind whipped sand through Inma Zanoguera’s hair and up her nose.

Camels lifted their heads, their long-lashed eyes following her as she ran by. Up and down the rocky dunes under the cloudy sky, The University of Toledo graduate student and former basketball player ran.

Based on last year’s winning time, Inma Zanoguera knew she had a shot at winning the Sahara Marathon — and she did, becoming the first Sahrawi to win the 26-mile race. (Photo by Damien Patard)

To while away the hours, Zanoguera filmed herself talking to her family on the GoPro she carried. She recited poetry. And she returned to her favorite running song, Kendrick Lamar’s “DNA”:

I got loyalty, got royalty inside my DNA…

Got war and peace inside my DNA

I got power, poison, pain and joy inside my DNA

I got hustle though, ambition, flow, inside my DNA

I was born like this…

This song meant a lot to Zanoguera on so many levels. It was her DNA that brought her to the desert, the birthplace of her biological mother. She was on a quest of sorts, a search for her roots.

Inma Zanoguera’s journey to Africa was about much more than the marathon. In her search for her roots, Zanoguera said she found more questions than answers. She said she relishes the connections she made with people in the camps, who were gracious and hospitable. (Photo by Michelle-Andrea Girouard)

The 2018 marathon was historic. For the first time, Sahrawis won both the men’s and women’s marathons.

A search for ‘home’

Adopted when she was a toddler by a family in Mallorca, Spain, Zanoguera discovered last year that her birth mother was a Sahrawi.

In 1975-76, Sahrawis fled their home in Western Sahara as Moroccan soldiers invaded during the Western Sahara War. Zanoguera’s mom was fortunate to land in Spain. But many others ended up in refugee camps in Algeria. They are still there, four decades later.

The marathon route traveled through three of the five refugee camps.

Zanoguera said she tried not to have any expectations of her trip to Africa. She wanted to remain open to whatever she saw and felt. A few weeks later, back in Toledo, she is still processing the experience.

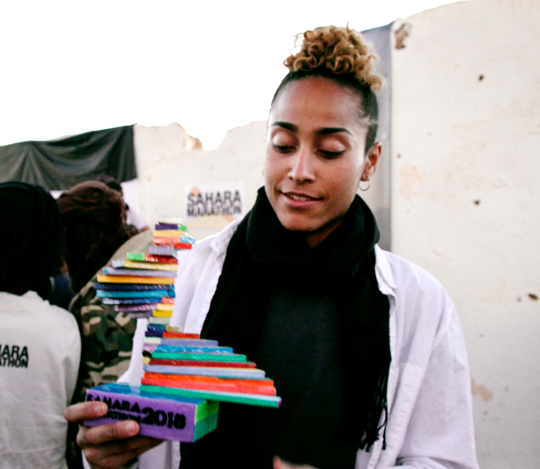

Inma Zanoguera looked at her award for winning the 2018 Sahara Marathon; the awards were made by artist Mohamed Sulaiman Labat, who lives in Smara, the refugee camp where Zanoguera stayed while in Algeria. (Photo by Michelle-Andrea Girouard)

“Those were big questions,” Zanoguera said.

She didn’t have ready answers.

The question of “home” has always been one that troubles her, she said. She never felt quite at home in Spain, where the only people who looked like her were her brother and sister.

She decided to come to America in part because it had black and brown people. But when she got here, she said she was still seen as “other,” as a foreigner.

“I never feel at home anywhere,” she said. “Part of me unconsciously wanted to find a home [on this trip to Africa].”

At the award ceremony the day after the race, Inma Zanoguera raised the Sahrawi flag, the flag of her birth mother’s homeland. (Photo by Michelle-Andrea Girouard)

“He welcomed me home,” she said. He told her he was happy to have her back, even though this was her first trip to her mother’s homeland. She was offered dual citizenship.

As she wandered the camps, she knew she stood out. Once again, nobody looked like her. She wasn’t wearing a melhfa, the traditional full body cloth that Sahrawi women wear. But at the same time, she said, it was like holding up a mirror to herself when she looked at them.

She said she was touched by their hospitality, their willingness to answer her questions. She had so many. “What do you think about someone like me coming to the camp and calling herself Sahrawi? How do you find meaning in the camps?”

Inma Zanoguera befriended 18-year-old Mohamed Moulud on the day of the race’s award ceremony. He convinced Zanoguera that she should raise the Sahrawi flag when she claimed her prize.

“The world has enough art,” he told Zanoguera. “They need me here.”

He built a studio in the camp and creates art out of whatever he can find — wood, cloth, clay, metal. He made the colorful, creative awards that Zanoguera and the other runners received.

Zanoguera said she thought she might have some kind of mystical revelation as she ran. She didn’t. But one evening at sunset, her guide took her and Canadian filmmaker Michelle-Andrea Girouard, who is making a documentary about Zanoguera’s search for her roots, to the dunes near the camps.

As she gazed out over the endless horizon, Zanoguera said she had a moment of sadness. There isn’t much beauty in the camps, she said, but here, there was indescribable beauty.

“I realized that the beauty, the oil, the [natural resources] were so out of reach for those who belong to the land. They didn’t get to enjoy this,” she said.Finding her place

The marathon and the connections she made to her mother’s people were healing for her, Zanoguera said.

“This trip was part of the learning process and acceptance,” she said. “I am Spanish, and I am Sahrawi, and I feel like a part of me also is American because I came here at such a young age. I am all these things, not just one.”

She said she has more questions now than when she started.

“I don’t know yet what it means for me and how it will affect my daily life,” she said.

Zanoguera and Girouard raised $1,200 for the refugees. Zanoguera said the two want to be smart and use it to create a sustainable program for the refugees. They’re considering starting a sports program for children, a way to distract the kids from life in the camps and share the many lessons that Zanoguera learned from athletics.

Her new friends in the camps asked if she was going to come back to visit. Zanoguera said she’s not sure. She said she would love to come back when their film is finished and present it at FiSahra, the film festival the camps hold each year.

Celebrating her victory

At the award ceremony the day after the marathon, Zanoguera leaned against a fence as she waited to receive her prize. She was torn. She’d never really felt a strong allegiance to any flag. When she played basketball for the Spanish national team, she said it never felt right to her to raise the Spanish flag.

But here, among the Sahrawi people, it felt right to raise the Sahrawi flag.

“But how do you dare raise a flag that signifies so much persistence and honor after only three days of being in this camp?” she said.

As she waited, she struck up a conversation with Mohamed Moulud, an 18-year-old refugee, who stood on the other side of the fence. She asked him what he thought. Would he be offended if she raised the Sahrawi flag?

“You absolutely must,” he told her.

She turned to the crowd and asked to borrow someone’s Sahrawi flag. As she walked to the stage — the first Sahrawi woman to win the Sahara Marathon — she carried the flag of her mother’s country and raised it high.