Wind turbines to generate electricity are sprouting up coast to coast, as are concerns over their effect on bird populations. Now that turbine developers are exploring sites along Ohio’s lakeshore — with its teeming waterfowl population and famed songbird migration routes — the need for solid research on the issue becomes apparent.

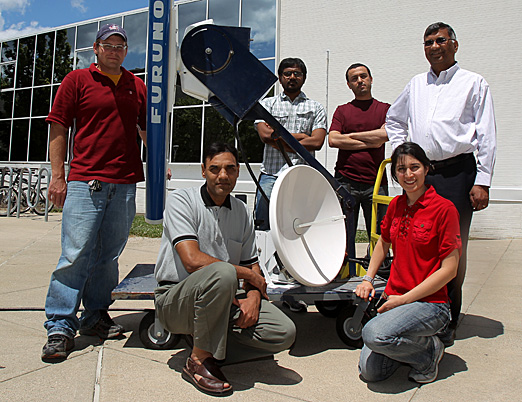

Providing technological support for BGSU researchers to collect data on bird and bat migrations are, from left, Dr. Jeremy Ross; UT engineering students Mohammad Wadood Majid, Vamshi Gummalla, Amin Jarrah and Golrokh Mirzaei; and Dr. Mohsin Jamali, who posed with project equipment.

Dr. Mohsin Jamali, UT professor of electrical engineering and computer science, explained the three-pronged approach the department is taking to assist BGSU researchers: “We’re using acoustics, recording the bird and bat calls for analysis. Then infrared photography provides the X and Y coordinates — where the animals are. Finally, modified marine radar gives information that includes elevation and travel velocity.”

The goal, he added, is to design a comprehensive monitoring system, then miniaturize it for use in offshore turbines so that migration data can be continuously transmitted to researchers. Presently, the equipment is carried from site to site in a small truck.

Dr. Jeremy Ross, BGSU wildlife biologist, has collected two seasons of data being analyzed by UT engineering. He spoke for this story after pulling an all-nighter assembling data in a deployment area at the mouth of Crane Creek in eastern Lucas County, on the border between Ottawa National Wildlife Refuge and Magee Marsh Wildlife Area.

As he explained, “We’re using these various tools to assess what’s going on at the lakeshore transition zone, an area known globally for songbird migrations. It’s also a breeding ground for other species.

“A lot of the expense of projects like this lies in analyzing the data. We don’t have the staff to spend hundreds of hours tracing by hand the blips on a radar screen that represent birds or bats, so we needed the development of an algorithm that could track the blips and provide the heading, altitude and relative size of the target. That’s where the computer engineering comes in, being able to deal with many gigabytes of data.”

“Jeremy tells us what he wants to see, then we produce it,” added Jamali, who has nearly a dozen doctoral, master’s and undergraduate students working with him. “We’ve developed software in-house that’s superior to the commercial version.”

In the process, the team may end up creating technology less expensive than typical monitoring equipment, making it attractive to other research teams with relatively small budgets.

Jamali noted that applications for the software go further. He’s involved in a bird strike project, which addresses the increasingly headline-grabbing problem of collisions between aircraft and birds or bats in flight.

“All the work on this project is applicable to bird strikes as well,” Jamali said, adding that he’s working on a related proposal with Dr. Peter Gorsevski of BGSU, the principal investigator for the turbine project. Drs. Joe Firazado and Vern Bingmant are the other BGSU team members.

Wind turbines will become common in this area, Ross said. “It’s important to have the facts early so that animal migrations can be addressed. Ohio is taking the right tack by emphasizing pre-assessment before wind turbines are built.”