It is the movie of the holiday season. Stephen Spielberg’s “Lincoln” is being talked about as an Oscar contender, particularly for Daniel Day Lewis’ haunting portrayal of the 16th president.

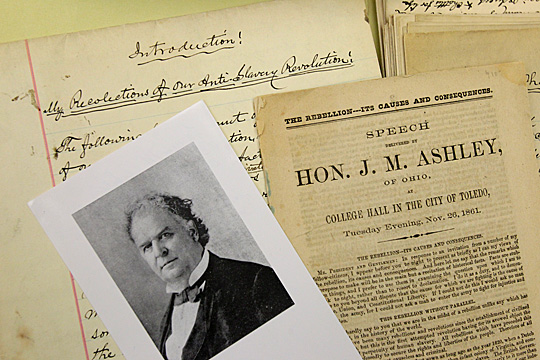

The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections holds the personal papers of James Ashley, the congressional representative from Toledo who drafted the 13th Amendment to abolish slavery.

In one of the most spellbinding scenes of the movie, Ashley introduces the amendment for its vote before the House. As each congressman registers his aye or nay, the House and the gallery anxiously keep count to see if the amendment will get the two-thirds vote needed for passage. When the amendment is finally passed by three votes, the emotional outpouring of both those in favor and against is historical drama at its best.

What viewers may not know is that Congressman Ashley, who not only introduced the amendment for the vote but helped to write it, was the congressional representative from Toledo. What remains of Ashley’s personal papers are preserved in UT’s Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections.

As a young boy, Ashley ran away from home and got a job working on the steamboats on the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It was here that he first encountered the horrors of slavery that would inspire his later efforts to abolish it. Ashley became editor of the Portsmouth, Ohio, Democrat newspaper in 1848, and a lawyer a year later.

In 1851, he visited Toledo and decided to settle in the growing city. But while he tried his hand at newspaper publishing, even establishing a drug store on Summit Street, his real interest was in public service. He was active in the Democratic Party in Lucas County and frequently spoke out against slavery.

Ashley’s anti-slavery beliefs and his concern that slavery would spread throughout the nation’s Western territories moved him to the Republican Party, and in 1856 he served as a delegate to the party’s national convention. His strong abolitionist beliefs earned him the label “Radical Republican.” He argued that the Constitution never intended that men be recognized as property.

In 1858, he was elected to Congress from Ohio’s fifth district, which included Toledo. He was re-elected in 1860 and that year campaigned for Lincoln’s election to the presidency, helping him to carry Ohio.

Ashley would be re-elected two more times during the Civil War, in 1862 and 1864. His popularity led him to work for what he saw as his most important goal: the abolishment of slavery. Ashley knew the only way to accomplish this was by amending the Constitution because President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was a wartime act. When the war ended, slavery likely would return without a constitutional prohibition against it. That led Ashley to propose the first constitutional amendment to ban the institution in 1863. The language that Ashley drafted would be nearly identical to that which would eventually be passed in 1865 as the 13th Amendment.

After his triumph in passing the amendment, Ashley was re-elected to Congress in 1866. But his radical — some would say fanatical — views led him to initiate plans to impeach President Andrew Johnson. He was defeated in his bid for re-election to Congress in 1868 and moved to Montana, where he was appointed territorial governor by President Ulysses S. Grant. But his criticism of the president led to his removal from that post within a year, and he returned to Toledo in 1872. In his later life, he purchased and operated the Toledo, Ann Arbor and Northern Michigan Railroad.

In 1896, Ashley began to write his memoirs. His papers in the Canaday Center consist of handwritten drafts of these memoirs that cover several topics, including the development of his political philosophy and the operation of his congressional campaigns. Because of a fire that destroyed his library, the papers in the Canaday Center are the only Ashley personal papers known to exist.

In the manuscript preserved in the Canaday Center, Ashley recounted when he first came to recognize the inhumanity of slavery. “My earliest recollection of the criminality of slavery was the impressions which came to me direct from the shocking scenes of the whipping post,” Ashley recalled.

He also told the story of a freed man from Kentucky who was captured and sold as a slave, then transported from Ohio to the deep South. As he was being sent away, Ashley said the slave turned to the man who sold him and said, “You seized and beat and chain and sell me. I am powerless and helpless, but when it comes time to stand before our Maker and Redeemer in the great day of Judgment, I would rather be in my place than in yours.”

The papers of Ashley are available to researchers interested in his life — a life that may, due to a Hollywood movie, finally come to greater attention.

Floyd is the director of the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections.