Feeling powerless to help her native country in Africa amid the coronavirus pandemic, an electrical engineer at The University of Toledo found a way for people in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) to build their own breathing machines from scratch using equipment and materials accessible to them.

Using Twitter, Dr. Ngalula Sandrine Mubenga, assistant professor of electrical engineering technology, tapped into her worldwide network of engineers with ties to the DRC and engineers and students inside the country.

Mubenga is the founder of the STEM DRC Initiative, a nonprofit organization that has awarded scholarships to pay all associated costs, including transportation and books, for more than 60 students in the Congo to go to college since 2018.

“There are less than 1,200 ventilators in a country with nearly 85 million people, and about 50 of those machines are in the capital city of Kinshasa,” Mubenga said. “Kinshasa will need a minimum of 200 ventilators by mid-May when COVID-19 cases are expected to peak in the Congo.”

In the DRC, there are more than 1,000 confirmed cases of coronavirus, more than 40 deaths caused by the new coronavirus, and about 3,000 suspected cases. An estimate last week showed the country had a maximum capacity of 200 tests per day for the whole country.

“When I was watching the news here in Ohio and heard the president of the United States announce that General Motors was going to build 100,000 ventilators, I thought, ‘What is going on in the Congo?’” Mubenga said. “We have the opportunity, means, technology and knowledge to do that here, but the Congo is a state that is rebuilding its infrastructures with very few factories for assembly.”

In three weeks, the team of about 20 people who answered her call to volunteer worked together — through videoconferencing and emails — and developed a prototype of a life-saving ventilator using open-source specs from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The working prototype next needs to undergo testing and certification, which Mubenga hopes to accomplish by the end of this year.

“It costs up to 30,000 U.S. dollars to buy a ventilator right now,” Jonathan Ntiaka Muzakwene, who teaches engineering on the faculty of Loyola University of Congo, said. “Dr. Mubenga is timely to respond to the needs of our country and help save lives.”

Mubenga teamed up with many partners, including a hospital in Kinshasa and the national trade school.

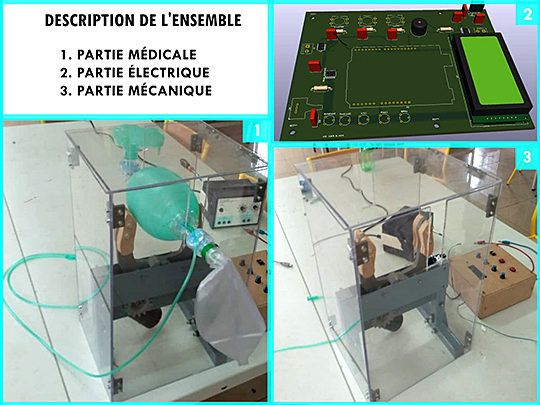

Dividing the team based on their talents, they built an emergency ventilator that makes use of Ambu resuscitator bags commonly hand-operated in hospitals by medical professionals to create airflow to a patient’s lungs until a ventilator becomes available. The new device includes a mechanism that automates the squeezing and releasing motions.

“Instead of having a doctor or a nurse pressing the bag manually, we have a machine pumping the bag so the patient can breathe,” Mubenga said.

Muzakwene and his engineering students inside the DRC made use of their school’s 3D printer in their work to fabricate, assemble, program and test the prototype, a process made more challenging because of troubles with internet access, expert resources, and unclear laws and standards for validation of the technology.

“All the materials, components, parts and equipment necessary for the production of these ventilators are difficult to find here on site in the DRC,” Muzakwene said. “The big challenge then is to find what we need to make these ventilators locally here in the country, challenges that the United States does not have.”

“All the materials, components, parts and equipment necessary for the production of these ventilators are difficult to find here on site in the DRC,” Muzakwene said. “The big challenge then is to find what we need to make these ventilators locally here in the country, challenges that the United States does not have.”

“A ventilator is very delicate,” Mubenga said. “You have medical, mechanical and electrical specifications that have to be met. And while MIT provided most of the design documents, it did not include the most important piece until very recently: the controls code of the model. We’re talking about how to get feedback from different sensors to the microcontroller and adjust the system based on that feedback.”

The controls adjust the timing and compression of the Ambu bag based on three main input parameters: the volume of air pushed into the lungs, the ratio between inspiration and expiration time, and the respiratory rate, or breath per minute.

The task is personal for Nicole Bisimwa, a student at Loyola University in Congo. She worries about friends, family and loved ones across the African country.

“The clinics of Ngaliema and university have only one ventilator each, which is sorely insufficient in case they have several patients who need it,” Bisimwa said. “Limiting international trade is a barrier to supply, but we continue to find solutions to overcome this problem. Any help is welcome.”

The project also is personal for Mubenga, who understands the life-changing power of technology. When she was 17 years old in the DRC, she waited three days for surgery after her appendix burst because there was no power at the hospital.

“I was living in a small town called Kikwit, far away from the big and beautiful capital city of Kinshasa,” Mubenga said. “I was very sick, doctors needed to do surgery, but they couldn’t find any gas to turn on the power generator. For three days, my life depended on electricity. I was praying. I could not eat. And decided if I made it alive, I would work to find a solution so people wouldn’t die because of lack of electricity.”

The hospital found fuel to power the generator, doctors did the surgery, and Mubenga survived.

Mubenga started studying renewable energy at the UToledo College of Engineering in 2000 and earned a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree and Ph.D. in electrical engineering. After receiving her professional engineer license in Ohio, she went on to found her company called the SMIN Power Group, which develops and installs solar power systems in communities throughout the DRC.

Mubenga next plans to test the ventilator prototype using software from the DRC that can be accessed online.

“We still have a lot to do, but this prototype is a big step,” Mubenga said. “We are putting together the clinical team of doctors who will provide feedback so we can improve the device. After that, we will proceed through certification. We have applied for funding to help spark production, but we’re committed to continue volunteering our time, talent and resources. Taking action to find a solution is our way to bring light in this dark, gloomy time. It’s the right thing to do.”