This summer’s 50th anniversary of the historic Apollo 11 moon landing also marks a major life milestone for The University of Toledo astronomer who is a world leader in her particularly male-dominated field.

“I was born in 1969, two months after Neil Armstrong took one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind,” Dr. Rupali Chandar, professor of astronomy, said. “I am delighted every time the anniversary comes up in July — the moon landing epitomized the human spirit of discovery, and that same spirit drives my research to understand our universe of galaxies.”

Dr. Rupali Chandar, professor of astronomy, was awarded 40 hours of observing time with the Hubble Telescope between July and early 2020. Her work will focus on star formation in nearby galaxies.

However, this year is extra-special for two reasons.

Chandar not only won coveted observing time in the most competitive cycle in history, she also leads the Space Telescope Users Committee.

Chandar heads the group of 12 astrophysicists from around the world who act as the direct interface between astronomers who want to use the telescope and top-level management of the Hubble project. Committee members hail from places with prestigious astronomical communities such as Harvard and Arizona State, as well as Paris, Spain and Italy.

She is the second UToledo astronomer to lead this powerful committee. Dr. Michael Cushing, associate professor of physics and astronomy, and director of Ritter Planetarium, led the committee in 2015 and 2016.

“It’s unusual for one university to have had more than one representative in the group — let alone two people who have led the committee’s work,” said Dr. Karen Bjorkman, interim provost and Distinguished University Professor of Astronomy. “Dr. Chandar is a shining star for women in science and contributes significantly to The University of Toledo’s research excellence in astronomy and astrophysics.”

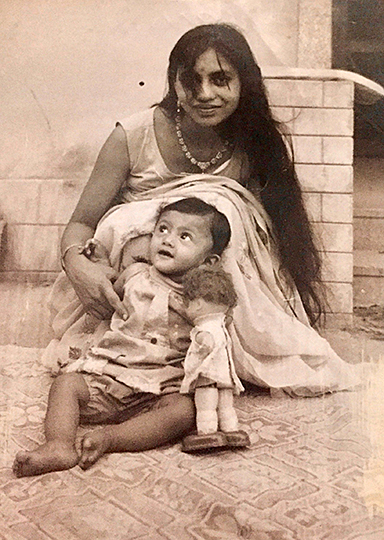

Even as a child, Dr. Rupali Chandar was looking skyward. She was born two months after the Apollo moon landing and is shown in this photo with her mother, Sneh Chandar.

“I’ve used Hubble data from the beginning of my career, and this cycle was the most challenging one in my experience, with only one in 12 proposals being successful,” Chandar said. “I am thrilled that my proposal was approved.”

As head of the Space Telescope Users Committee, she helped implement the dual-anonymous selection process that debuted this cycle, which means the names of the proposers and reviewers are made known only after the review process is complete.

“Hubble is leading the way in emphasizing the science and ideas that are proposed, and not who is doing the proposing,” Chandar said. “Although it’s too early to tell, this double-blind review process has the potential to reduce inherent bias.”

Chandar, a mother of two who joined the UToledo faculty in 2007, was awarded approximately 40 hours of observing time spread out between July and early 2020. Her work will help understand star formation in some of the most intensely star-forming galaxies found in the nearby universe.

And by nearby, she means those 130 million to 300 million light years away.

These galaxies are generating stars at a pace about 100 times faster than the Milky Way.

“In the modern-day nearby universe, most galaxies form stars at a modest rate,” Chandar said. “I will be observing a sample of the few actively merging, nearby galaxies that have rates of star formation that are as high as galaxies in the early universe. Studying them gives us insight into what was happening when the universe was young and galaxies were just starting to form.”

Astronomers can’t study details of star formation in early galaxies because they’re too far away. We’re talking billions and billions of light years.

However, astronomers believe new, more powerful telescopes in the pipeline, like the James Webb Space Telescope, will make it possible to study the evolution of the earliest stars in greater detail than ever before.

As Chandar looks ahead to the next 50 years of space exploration, it’s vitally important for her to inspire children, especially girls, to take the step toward science.

“Girls in elementary school are just as interested in science as boys. It’s alarming how much that changes during middle school,” Chandar said. “When I was in fifth and sixth grades, I read about the formation of the solar system and wrote reports about black holes, but I didn’t think you could do astronomy as a career until I took a class during my sophomore year of college.”

She ended up earning her Ph.D. in astrophysics at Johns Hopkins University in 2000.

“Good professors make a difference,” Chandar said. “Without many female astronomers around, my mentors have been almost exclusively men. Their support has been critical for achieving my dream career.”

Chandar has one more connection to the moon landing, besides being born in 1969.

“I was lucky enough to hear Neil Armstrong’s last public address at the July 21, 2012, First Light Gala to celebrate the debut of the Discovery Channel Telescope when The University of Toledo joined as a scientific partner,” Chandar said. “We were all devastated when Neil died just a few weeks after that.”

As part of the partnership, UToledo students and researchers use the Discovery Channel Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona to collect data on a wide variety of objects, from the closest failed stars known as brown dwarfs to star-forming regions within our own galaxy to more distant merging galaxies.

The 4.3-meter telescope located south of Flagstaff overlooks the Verde Valley and is the fifth largest telescope in the continental United States and one of the most technologically advanced.

The Discovery Channel Telescope partnership has been a boon to UToledo astronomers and helped put the astronomy department on the map.

“It’s another powerful tool at our fingertips to continue NASA’s mission and push technology to new frontiers over the next 50 years,” Chandar said.