Researchers at The University of Toledo are using clues from nature to engineer a potential solution to address the annual algal blooms that foul Lake Erie and hundreds of other freshwater lakes across the world.

The innovative project could lead to a new type of filter that would allow scientists to actively screen large amounts of blue-green algae from the water before it’s able to release cyanotoxins.

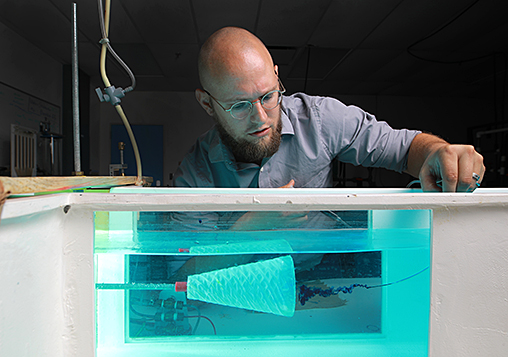

Dr. Adam Schroeder used dye to demonstrate how a filter inspried by the paddlefish works like a vortex to clean water. The conical cross-step filter could help collect algae from lakes.

With help from a College of William and Mary biologist, Schroeder and Dr. Brian Trease, assistant professor of mechanical, industrial and manufacturing engineering, focused on the paddlefish, a prehistoric-looking freshwater fish that lumbers through lakes and rivers with its mouth agape to collect nutritious zooplankton.

“They’re processing lots of water for minutes at a time to filter out food. We can take that concept and then expand it beyond what we see in biology,” Schroeder said.

The research team’s findings were recently published in the journal Bioinspiration & Biomimetics.

Dealing with harmful algal blooms requires a multidisciplinary approach. Researchers at UToledo are studying the health impacts of harmful algal blooms, developing new ways of filtering cyanobacteria out of water, and actively monitoring blooms in Lake Erie.

Schroeder, who earned a doctorate in mechanical engineering from UToledo in 2018, brings a different perspective.

“Somebody without any knowledge of the problem might say why can’t we just pick up the algae,” he said. “So why can’t we? It’s nice to explore that idea — what would we need to do to get rid of the algae?”

Currently, environmental scientists gathering algal samples use conventional-looking nets that have a small canister at the end to collect algae. The trouble with using those nets to remove large amounts of algae, however, is that they can only gather so much before they clog.

When the paddlefish feeds, its mouth creates a vortex of swirling water that helps it collect food indefinitely without its biological filters clogging. Using that concept, Schroeder developed a conical cross-step filter that mimics the paddlefish while adding creative engineering solutions.

Lab tests showed their design is able to transport suspended particles roughly the same size as the predominant Lake Erie algae downstream toward the end of the filter and is resistant — though not immune — to clogging.

The researchers’ next step is to develop a method for sequestering the particles after they exit the back of the filter. If they can do that and develop a method to remove what particles attach to the filter walls, it might be possible to create a filtering apparatus that can operate continuously in lake waters.

“We see this as a complementary solution. The real problem is that the algae is there in the first place. We have to stop all these nutrients from getting in the water, but that’s a really hard problem to solve and even harder to do it quickly,” Schroeder said.

In the meantime, he believes it is worth examining other, out-of-the-box ideas that might contribute to making lakes and rivers healthier.

“You don’t need to clean up the whole bloom, but maybe you need to keep a 500-meter radius clear of algae. That’s something we might be able to do,” Schroeder said.