New research from The University of Toledo confirms the significant, widespread physical changes that exist in the brains of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder.

The study, published in the journal Molecular Psychiatry, provides the strongest evidence to date of the structural brain changes across the entire cerebral cortex, including regions responsible for sensory processing. Understanding the physiological abnormalities present in PTSD patients may open the door to new methods for treating the mental health condition that affects an estimated 8 million Americans annually.

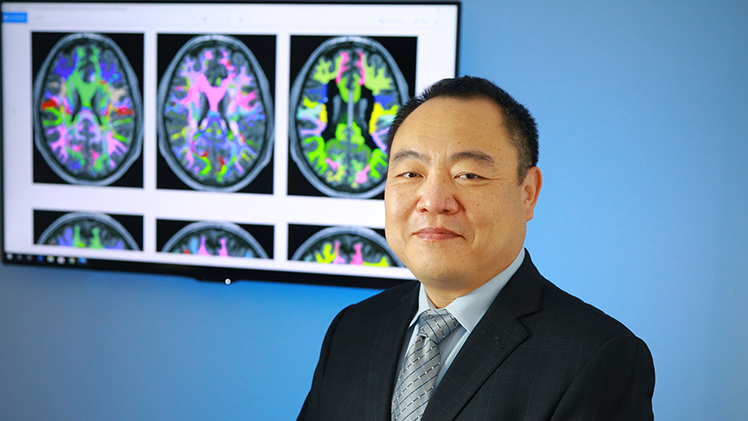

Dr. Xin Wang, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience in the UToledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences, led a UToledo research team that spent two years collecting structural MRIs from nearly 1,400 PTSD patients across seven countries.

“This study fundamentally changes what we know about how PTSD physically affects the brain,” said Dr. Xin Wang, professor of psychiatry and neuroscience in the UToledo College of Medicine and Life Sciences. “Patients with PTSD experience not only functional changes in how their brain works, but their brain structure has actually changed as well.

“Most of the research focus to this point has been on emotion-related areas of the brain. Some small studies have suggested sensory processing regions were also affected, but nobody has had a large data set to confirm those findings and also systematically look at where the structural change happened. This study is doing that.”

Wang led a UToledo research team that spent two years collecting structural MRIs from nearly 1,400 PTSD patients across seven countries. Using those three-dimensional scans, researchers analyzed 68 regions within the cerebral cortex and compared them to brain scans of nearly 2,200 individuals without PTSD.

The study — which relied on the largest mega-analysis to date — confirmed that PTSD patients experienced atrophy in several areas of the brain that regulate emotional response.

More critically, however, researchers also observed significant changes in several parts of the cerebral cortex that are responsible for processing sensory information.

For example, UToledo researchers found structural abnormalities in the lingual gyrus — a small region near the back of the brain that is involved in visual memory.

Wang said it’s possible those abnormalities may relate to the vivid flashbacks and nightmares that PTSD patients experience. The study also reported changes in a pair of areas that control the integration of auditory, visual and emotional processing. Structural abnormalities in those areas could play a role in the spontaneous, intrusive memories that can cause negative emotions in people with PTSD and other psychiatric disorders after experiencing trauma.

“This is an angle that researchers haven’t really looked at before in PTSD and we found it very consistently across our entire sample population,” Wang said. “This study opens a new field for PTSD researchers.”

One intriguing implication of Wang’s work could be a shift in how PTSD is treated. Currently, most treatment is focused on emotional regulation and helping patients understand their experiences. With strong evidence that areas of the brain tied to processing sensory input and sensory memory are also affected in PTSD, clinicians may be able to target the condition in new ways.

“Very few treatments target how patients process sensory information. This evidence from a biological aspect can really help therapists think about additional treatment from new ground,” Wang said. “Better understanding both the functional and structural changes that underlie PTSD symptoms may provide new targets for both behavioral and pharmaceutical treatments.”