Carmen Williamson didn’t go down without a fight.

The 94-year-old student at The University of Toledo and one of the nation’s top amateur boxers during the 1940s and 1950s lost his last bout in a hospital room.

CELEBRATING SUCCESS: During this time when we cannot come together to celebrate our graduates, UToledo is recognizing the Class of 2020 with a series of feature stories on students who are receiving their degrees. Help us celebrate our newest UToledo alumni. Visit utoledo.edu/commencement to share a message of support to graduates and come back online Saturday, May 9, to take part in the virtual commencement ceremony.

Williamson, who eventually hung up his boxing gloves and traveled the globe as a prominent judge and referee representing the United States during Olympic and World Championship competitions, died last week from COVID-19, less than a month shy of graduation.

The first African-American man to officiate boxing in the Olympics — for which he received a gold medal in the 1984 Olympic Games — was scheduled to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies from University College on May 9.

Williamson has five daughters, including Dr. Celia Williamson, Distinguished University Professor and director of the UToledo Human Trafficking and Social Justice Institute.

“My dad loved education and was so proud to be finally getting his degree,” she said. “He was very strong. He fought lots of fights through the decades. He was living his best life – still driving and going to school and independent.”

Celia last saw her dad in March when Toledo City Council recognized him as part of Black History Month with a proclamation honoring his achievements.

Carmen Williamson, 94, right, was recognized in March by Toledo City Council with a proclamation honoring his achievements as part of Black History Month celebrations. His daughter, Dr. Celia Williamson, UToledo Distinguished University Professor, joined him at the council meeting.

Born in Toledo in 1925, Williamson was raised by a single mom. He dropped out of high school to work and help the family.

“Back then there weren’t any avenues for young black men. Boxing was a way out of the streets that also taught you discipline and nutrition,” Celia said. “They lived in a high-crime area where it was pretty dangerous in poverty and racism. Instead of getting himself in trouble and to protect himself from trouble, he used his time to box.”

The 112-pound boxer ended his amateur career in the ring with a record of 250 wins and 14 losses.

Instead of pursuing a professional career, Williamson started working with troubled youth in the community and trained them to be boxers.

“Many were successful and owe the positive turn in their life to their mentor and coach,” his daughter said.

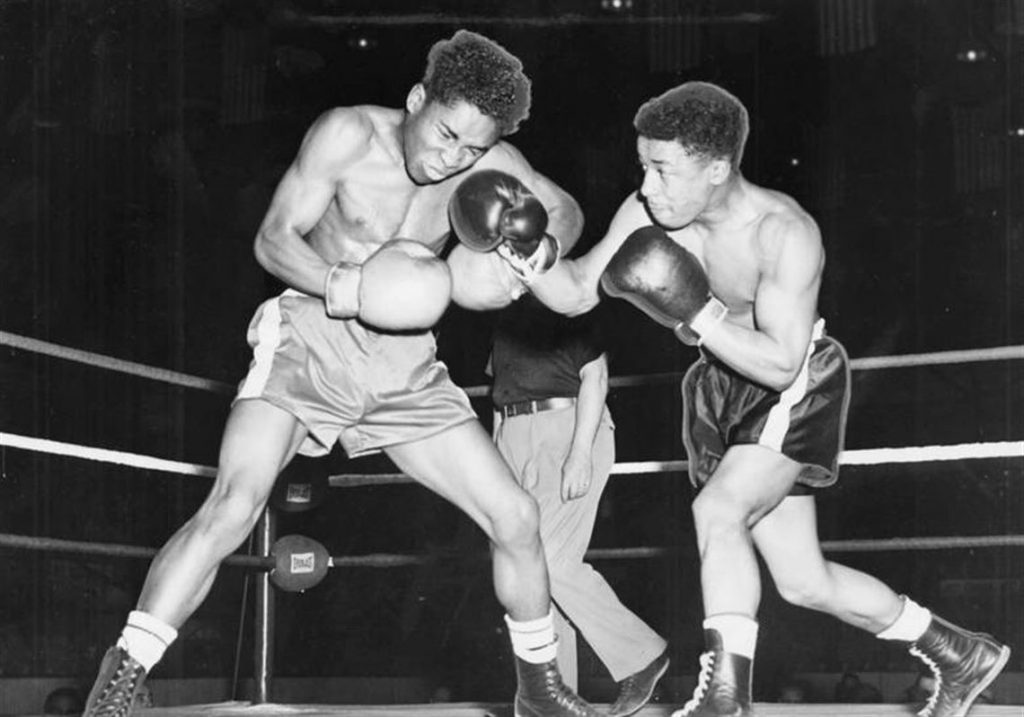

Carmen Williamson, who was preparing to graduate from University College with a bachelor’s degree in liberal studies, right, was one of the nation’s top amateur boxers during the 1940s and 1950s. He went on to serve as a prominent judge and referee representing the United States during Olympic and World Championship competitions.

Williamson, who served in the U.S. Navy and later earned his GED in his 60s, retired after working for nearly half a century as a civilian employee for the U.S. Army’s automotive tank division in Warren, Mich.

“He had a desk job. He wore a suit and tie to work every day,” Celia said. “He worked for 42 years and only missed two days of work. At his retirement party, his co-workers joked, ‘If there was a blizzard, Carmen would be here.’ He was happy to have a job and get his GED.”

In the 1980s, Williamson became involved with USA Amateur Boxing.

He developed a curriculum and began to travel all over the world teaching the sport to young men and preparing them to compete with other countries.

“My dad visited nearly 100 countries, but I’m especially proud that he volunteered to take on assignments in dark, warn-torn countries like Sierra Leone,” Celia said. “White trainers wouldn’t go there, so he trained African and Caribbean men to compete.”

In 1984, Williamson officiated the Olympic Games in Los Angeles and was given an honorary gold medal as the first African-American official to receive this honor.

In 1984, Carmen Williamson officiated the Olympic Games in Los Angeles and was given an honorary gold medal. He was the first African-American official to receive this honor.

“He has helped countless young men in Toledo and all over the world find focus and discipline in their lives,” Celia said. “His Olympic gold medal is a symbol that he achieved greatness. My dad is my hero and an American hero.”

But he wasn’t done. In 2000, the 74-year-old recipient of the African-American Sports Legend Award went to college.

“My dad first wanted to make sure he paid for my college before it was his turn,” Celia said. “He just wanted the education. A degree from The University of Toledo was the goal. I remember he took an Africana studies class and flew to Africa to look around, bring things back and give them to the class. He would sit in the front row. He loved education.”

During his last semester, the coronavirus pandemic spread to the United States and Toledo.

As campus closed and professors starting teaching classes remotely, Williamson was in and out of the hospital. At first, doctors thought he had a rare kind of pneumonia.

“When we found he tested positive for the coronavirus, doctors tried experimental drugs,” Celia said. “He did have diabetes, so I think his age and condition contributed to what happened. But it was a terrible situation. We couldn’t be by his side. The doctors and nurses were his family for the end.”

Celia and her sisters, left to grieve while social distancing, plan to host a memorial service once the pandemic clears and everyday life resumes.

But it turns out their dad did leave them one more success to celebrate.

The Provost’s Office will be asking the UToledo Board of Trustees at its next meeting to award Carmen Williamson’s degree posthumously.

“I was disappointed for him because he was there. He was taking his final three classes,” Celia said. “But he did it. Living or dead, doesn’t matter. He’ll have the degree he earned. That’s what he always wanted. We are grateful and hope he inspires another generation to work hard and take care of themselves and their families.”