The average person encounters cosmic rays when the fast, tiny particles shoot through the clouds and cause bright pixels on photos. Very few actually reach the ground, and they are not known to be harmful.

Astrophysicists long believed those lightweight protons or electrons moving close to the speed of light reach Earth’s atmosphere after supernova explosions, deflecting off electromagnetic fields in their scrambled path through space that ultimately masks their origin.

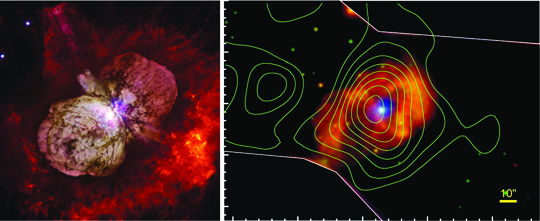

The left panel shows the Hubble image of Eta Carinae, and the right shows an X-ray image from the Chandra X-ray Observatory on the same scale. The green contours show where NuSTAR detected the very high-energy source, which also proves that it is Eta Carinae and not another source in the region. The images are courtesy of NASA.

The Eta Carinae discovery, which was published this week in the journal Nature Astronomy, was made by an international team, which includes an astronomer at The University of Toledo.

Dr. Noel Richardson, postdoctoral research associate in the UT Department of Physics and Astronomy, analyzed data from NuSTAR observations of Eta Carinae acquired between March 2014 and June 2016. The space telescope, which was launched in 2012 and can focus X-rays of much greater energy than any previous telescope, detects a source emitting X-rays above 30,000 electron volts at a rate of motion approaching the speed of light.

“Most stars can’t produce that much energy,” Richardson said. “Eta Carinae is one of only three star systems NuSTAR has been able to observe. The new technology allowed us to push what we understand about the high-energy universe. And we discovered that we don’t always need an exploding star, but rather two stars with massive winds pushing out cosmic rays.”The raging winds from Eta Carinae’s two tightly orbiting stars smash together at speeds of more than six million miles per hour approximately every five years. Temperatures reach many tens of millions of degrees — enough to emit X-rays.

“Both of Eta Carinae’s stars drive powerful outflows called stellar winds,” Dr. Michael Corcoran, team member at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, said. “Where these winds clash changes during the orbital cycle, which produces a periodic signal in low-energy X-rays we’ve tracked for more than two decades.”

“We know the blast waves of exploded stars can accelerate cosmic ray particles to speeds comparable to that of light, an incredible energy boost,” said Dr. Kenji Hamaguchi, astrophysicist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md., and lead author of the study. “Similar processes must occur in other extreme environments. Our analysis indicates Eta Carinae is one of them.”

Eta Carinae’s primary star is almost 100 times more massive and five million times more luminous than the sun. That star also is famous for losing 10 suns worth of material — huge amounts of gas and dust — into space in an enormous explosion in the 1830s that briefly made it the second-brightest star in the sky.

Richardson studies massive stars and also was part of the international team that captured the first sharp image of Eta Carinae’s violent wind collision zone and discovered new and unexpected structures in 2016.

In addition to UT and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, researchers from the University of Maryland in Baltimore County, Catholic University of America, California Institute of Technology, University of Leeds, Hiroshima University, University of Utah and San Jose State University contributed to the new study.

Read more and see a video here.