A football, bike helmet, hacky sack and plastic bottles are great for picnics and outdoor fun, but they are not so great for waterways.

On a recent blazing summer afternoon, near the parking lot of the north Toledo Menards, 1415 E. Alexis Rd., a trio of seniors in environmental engineering at The University of Toledo, joined Dr. Defne Apul, professor and chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, to remove the items that had somehow found their way into Silver Creek as well as more common litter and trash as part of a UToledo research project in collaboration with the city of Toledo and other partners.

From left, Elly Filas, Ethan Eidt, Dr. Defne Apul, professor and chair of the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Saee Gunjal sort through litter collected on the surface of a north Toledo creek through a device called a “trash trap.”

Using a “trash trap,” a floating device that sits on top of the water and collects the trash and litter on the water’s surface as it streams down the creek, Saee Gunjal, 21, Ethan Eidt, 21, and Elly Filas, 23, sifted through what was fished out of the creek before it got to Lake Erie, and then sorted it by type and counted the totals in each category.

There were 2.29 pounds of plastic, 2.51 pounds of foam and nearly 3 pounds in the category of “other” — mostly the sports equipment. In total, nearly 8.5 pounds of trash was removed from Silver Creek.

“This is the first haul that we’ve gotten that had plastic bags in it,” Filas said.

And with the general rule that plastic begets plastic — meaning plastics like large plastic bottles produce microplastics in the water that humans and animals ingest — any plastic in our lakes, rivers and streams will significantly impact us through a chain of events.

“You think, ‘This is so clean. I’m drinking clean water,’ ” Filas said. “It’s not. It’s got microplastics in it. The beer that you got at the bar? There are microplastics in it. There’s waste in everything that you’re drinking now because we’re not taking care of the trash properly.

“It makes you think, ‘Do I need to use this plastic fork or should I use my fork at home?’ ”

While the trash trap litter removal is important in the short and long term, cleaning the area’s waters is a positive byproduct of the students’ project: They are analyzing where the trash in the area’s water is originating — commercial, industrial, residential or parkways.

And since the city of Toledo also wants to know where and how the waste is getting into the water and eventually into Lake Erie, a partnership with UToledo students is ideal.

“The city of Toledo is excited to be one of the first cities on the Great Lakes to install multiple trash trap devices on waterways that lead to Lake Erie,” said Edith Kippenhan, senior environmental specialist in the city of Toledo’s Division of Environmental Services.

“Working with our partners, Partners for Clean Streams and UToledo, our project will not only ensure that much of the trash is stopped from making it to Lake Erie, it will also help us to gain a better understanding of how trash moves from the city to the waterways to Lake Erie, and determine some of our options to do better to stop the problem at its source.”

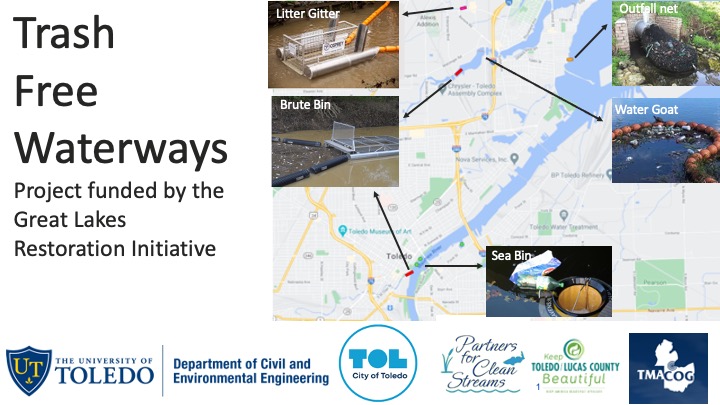

This map shows the names and locations of the different trash-gathering devices to be used as part of the UToledo research project in collaboration with the city of Toledo and other partners.

Even on a hot day, removing and cataloging the river waste is relatively easy in comparison to the research that went into building the project, such as how to best collect the trash.

“We knew that there were five kinds of devices the city is buying to install” in the area waterways, “and we had to figure out everything else,” Gunjal said. “We started figuring out what protocol we had to use.”

They settled on the EPA’s Escaped Trash Assessment Protocol (ETAP) Free Waters program, a survey tool that provides a standard method for collecting and assessing litter data, because it best fit their needs. Even after the students were trained on ETAP, they were still faced with challenges.

Most of the studies and information available focus on coastal and marine litter — not on lakes and the litter-feeding process via local waterways.

“These kinds of projects are really new,” Gunjal said, “and a lot of innovation is happening. A lot of cities are picking up on projects like us. We are definitely sort of pioneers in this, especially in the United States.”

In fact, because their project is so new, Eidt said, “We have to figure out the problems, which we then have to figure out how to solve.”

Funded through a two-year grant from the city of Toledo, the research project includes the deployment of five separate trash-collecting devices strategically located in the area, Apul said.

And given all the layers of this research project, including working directly with subcontractors and the city, she was specific in the students she recruited.

A football, soccer ball and bike helmet was among the nearly 8.5 pounds of trash removed from Silver Creek.

“I really wanted to get some students who cared about the problem, had good communication skills, good research skills and analytical skills,” she said. “And we’re writing a paper, so they have to have good technical writing skills as well. That’s why we have these three students.”

Gunjal, Eidt and Filas will continue working on the research through fall semester, with the plan to incorporate this project into classwork for other students.

“I envision we’ll have a dozen students involved in this project before it wraps up,” Apul said.

While Gunjal and Eidt are working on this as a co-op and Filas is taking this as a class, the trio share the same enthusiasm for their research and the benefits it will engender.

“I always knew that I had to do something related to the environment focusing on water because it’s essential,” said Gunjal, an international student from India. “Everyone needs water. I was very glad to have this opportunity to create an impact right now that’s going to last into the foreseeable future.”

As Eidt pointed out, 22 million pounds of plastic end up in the Great Lakes each year.

“When I found out that number, I was astounded,” he said. “If these systems actually are effective at capturing plastic, we might see a lot more installed in the Great Lakes region and hopefully we can get that number down.

“And also raise awareness — if for nothing else, because prevention is the best way of solving this. People not littering would definitely be the best preventative measure.”