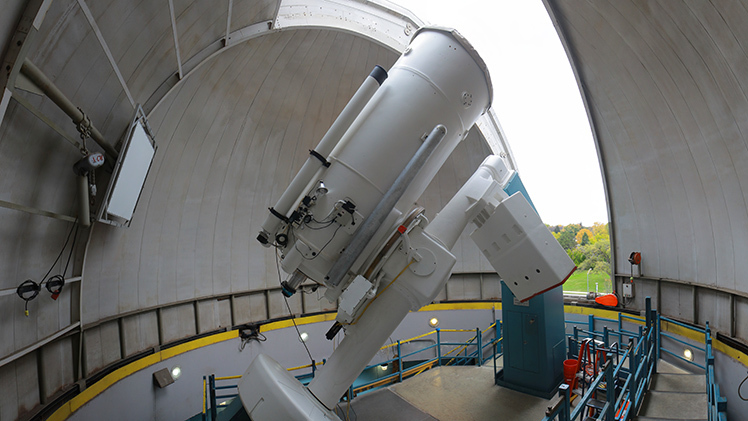

It’s no small thing to repaint a research-grade telescope.

First you need to disassemble it – very carefully, given that the whole apparatus weighs in at 30,000-some perfectly balanced pounds. You need to remove the 1-meter mirror, so you can send it off to be re-aluminized, and then you need to bring in a contractor to sand down each piece that remains.

It took less than a year to refurbish Ritter Observatory’s research-grade telescope.

And that’s all before anyone cracks open a can of paint.

The whole production took just under a year at The University of Toledo’s Ritter Observatory, said Dr. Jon Bjorkman, observatory director and a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy.

“It’s more than a fresh coat of paint,” he said. “We took on this project to protect the mechanical integrity of the telescope. So long as we maintain it, we’ll still be using it for hundreds of years.”

His department is excited to finally count the project completed and welcome back student observing teams who make use of the massive telescope on clear nights. Each team consists of one graduate student and three or so undergraduate students who are encouraged to get involved in research as early as their freshman year. Observing teams have been on hiatus since 2020. The pandemic claimed two years, on account of the tight quarters of an observing room that doesn’t allow for social distance, and maintenance to the telescope claimed a third.

“Next semester we’ll be in full swing,” said Bobby Stiller, who will be coordinating the observing teams as the observatory’s research assistant. “I’m excited to get started. It’s been a long time.”

Stiller anticipates at least 20 undergraduate students will sign on to observe at least one night each week. How often they actually make it up to the dome will depend on how frequently their chosen day of the week coincides with clear conditions. Their objectives throughout the semester will range from “pretty pictures,” particularly as they begin to learn the ins and outs of the telescope, to legitimate research.

“We require our undergraduate astronomy majors to complete a research project to graduate, and the observing teams are a good first step,” Bjorkman said. “They learn how to use the telescope and how to analyze what they see using computer programs, and they pick up some of the other skills they need in order to undertake their research projects typically in their junior and senior years.”

Student and faculty researchers are the primary users of the 1-meter Ritchey-Chretien reflecting telescope, which is outfitted with cameras and spectrographs. Bjorkman said it’s well suited for stellar observations, whereas researchers who focus on other areas generally turn to off-campus equipment including the Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes.

When the Ritter Observatory was dedicated in 1967, funded by a donation by local lawyer George Ritter, it was the largest optical telescope in the United States east of the Mississippi River. The Warner and Swasey-constructed telescope also stood out for its novel use of Cer-Vit, a glass-ceramic material designed to expand and contract very little by Owens-Illinois in Toledo.

The apparatus is significantly larger and more advanced than its counterpart in the neighboring Brooks Observatory atop McMaster Hall. That telescope is used for introductory astronomy classes and public outreach, including open observation following evening planetarium shows on most Fridays.

(The Ritter Observatory welcomes post-planetarium visitors only on the first Friday of the month.)

Stiller, a fourth-year doctoral candidate in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, is now very familiar with the telescope in the Ritter Observatory. He assisted in disassembling it, and in driving its mirror to Ithaca, N.Y., where specialists chemically stripped off its old aluminum coating and added a new one using a massive vacuum chamber they place the mirror inside.

As Stiller considered graduate programs in astronomy, the telescope proved an attraction to UToledo. He had experience with a similar telescope as an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame, and knew he wanted to continue observing on campus as he pursued his doctorate.

The telescope doesn’t support his specific research, which is testing atmospheric models of brown dwarves in the Hyades open cluster. For that he and his advisor, Dr. Michael Cushing, a professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy, need “bigger telescopes and darker places,” like the Gemini Observatory in Hawaii.

But it’s just right for a special night under the stars – especially now that it’s back in top shape.

“It’s a very different experience compared to the telescope in Brooks Observatory, or even the kind you would buy for personal use,” Stiller said. “It’s just fun to be up there and use it.”