Born in the Dominican Republic and raised in Brooklyn, Dr. Ayendy Bonifacio was 6 years old and his brother 4 years old when they arrived in the United States with their parents.

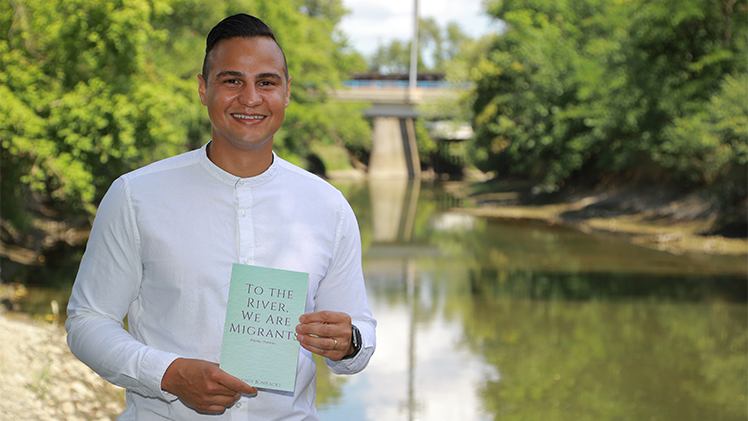

Now a 33-year-old assistant professor of U.S. ethnic literary studies at The University of Toledo, Bonifacio’s debut bilingual collection of poetry, “To the River, We Are Migrants,” helps us better understand what it means to be a migrant in these turbulent times.

The book, scheduled to be published Tuesday, Dec. 8, is available for pre-order.

Dr. Ayendy Bonifacio’s new book of poetry, “To the River, We Are Migrants,” will be published Dec. 8.

Throughout the poems that are presented in both English and Spanish, the river is a stand-in for migrant struggles and crossings, carrying us to and away from home through childhood, exile, faith and grief.

“Much of ‘To the River, We Are Migrants,’ like all of my writing, is shaped by my own immigrant experience and that of my family’s,” Bonifacio said. “I wanted to capture through a bilingual collection what it is like to mourn a country, a religion, a language and a father.”

José Julian Bonifacio, Ayendy’s father who established his own taxi business on Long Island, died in 2019 after a battle with brain cancer.

In the book’s introduction, Octavio R. González, poet and associate professor of English and queer studies at Wellesley College, said, “Ayendy Bonifacio carries generations of his family, his tongue telling their stories in two languages, his heart in two places, cleaved by duty and memory. The rosary which is the river connects him to that sacred place, origin and return, father and son, mother and grandmother, grandfather and holy father.”

González calls Bonifacio’s bilingual approach “inventive” because the poems are not translations.

For example, compare one line in English when the speaker, a boy, explains his odd scar — “ ‘It’s a vaccination I got when I was / a little kid in DR,’ I used to say” — to its corresponding line in Spanish — “ ‘Es una vacuna que recibí / cuando era niño en la República Dominicana.’ ”

“We can hear the clipped, boyish dialogue spoken in plain English, a cultural translation that becomes a small souvenir of a transplanted childhood spent in a Brooklyn schoolyard,” González said. “In Spanish, we instead hear the grandeur of Ayendy Bonifacio’s natal country — and mine — in all its accented syllables, a rhetorical flourish alien to the clipped sentences of American English. It’s a striking contrast to the speaker’s demure silence, which follows the American boy’s taunting reply, and ends the poem.”

Bonifacio said the collection is represented by two poems: “River Piedra” and “Mi Taita.”

“The first poem is about migrant experiences in the U.S. and the second about the memory of my late father,” he said. “These topics, among others, are behind the inspiration of this book.”

Bonifacio said he has a sense of political urgency, especially for the hundreds of migrant children whose parents the federal government cannot locate after being separated upon arrival in the United States at the border with Mexico.

“We cannot forget the 545 migrant children,” he said. “That number haunts me, and it should haunt you too. Their story isn’t mine and neither is their trauma. But the country I pledged allegiance to did this. It lost their parents. And we must do something. Their immigration story should not end with separation.”

Bonifacio’s memoir, “Dique Dominican,” was published in 2017.