When golden-winged warblers and their sweet, buzzy voices take flight on the long journey south wearing what look like miniature backpacks, Gunnar Kramer worries how many will return in the spring.

“These birds are very uncommon and have been declining severely in some parts of their range for more than 50 years — more than most other species of birds in North America,” Kramer said. “To help preserve them, we are learning exactly where they go for the winter and how they get there.”

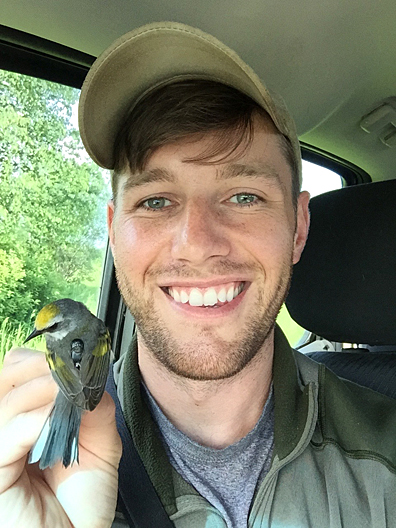

Gunnar Kramer held a golden-winged warbler, which carried a geolocator. Researchers attached the tiny backpack to the bird in 2015 and recovered it in 2016. The data on the geolocator will help Kramer understand the warbler’s migratory route and winter location.

The songbirds, which are about the size of a pingpong ball and weigh less than three pennies, travel thousands of miles, and Kramer is mapping their journey using what are called light-level geolocators.

“Golden-winged warblers breed throughout the Great Lakes region and the Appalachian Mountains,” Kramer said. “We know they spend the winter somewhere in Central and South America. However, nothing is known about where specific populations settle down.”

The graduate student in the Department of Environmental Sciences recently was honored for a talk he gave at the North American Ornithological Conference in Washington, D.C., about his pioneering research on the silvery gray birds with yellow-crowned heads that are under consideration for federal endangered species protection.

The American Ornithologists’ Union awarded Kramer the Council Student Presentation Award at the gathering of 2,000 birding professionals from all over the world.

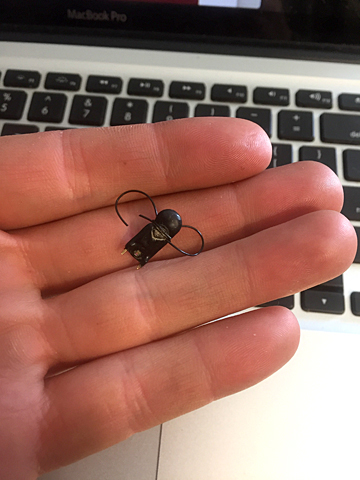

This geolocator was recovered from a golden-winged warbler after a full year of recording data. The bird carried this unit for more than 5,000 miles.

Kramer and Dr. Henry Streby, UT assistant professor and ornithologist, have been looping tiny backpacks around the legs of these birds for three years.

Figure-eight harnesses secure the backpack, which contains a battery, a computer chip and a light sensor. The whole thing weighs less than half of a paper clip and does not inhibit flight or movement.

“We were the first people to put this type of technology on a bird this small,” Streby said. “We developed the tiniest methods for the tiniest birds, and now we’re helping people do the same thing with many other species.”

“The light sensor records ambient light and stores it with a time stamp on the unit every couple minutes,” Kramer said. “We are using differences in day length to predict daily location of the birds throughout the year. Based on how long the day and night are, you can tell approximately where you are on the planet.”

So far, more than 100 light level geolocators have been recovered from birds who made the return journey to various locations up north.Though the research is not complete, preliminary results show golden-winged warblers from declining populations spend their winters in South America on the border of Venezuela and Columbia. The stable population of the species who breed in Minnesota spend the winter spread out through Central America from southern Mexico down to Panama.

“There might not be anything we may be able to do up here on the breeding grounds to help preserve this species of warbler if the limiting factors for these populations are on the wintering grounds,” Streby said. “Factors like loss of habitat or human disturbance might be influencing the populations in the wintering grounds to a different effect. Countries have different conservation policies. There are countries that can afford to take care of bird habitat and those that cannot. We have a responsibility to help them.”

These UT researchers are collaborating with scientists from various universities, including the University of Tennessee, the University of Minnesota and West Virginia University.

Funding is provided by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Geological Survey and the National Science Foundation.

Click here to watch a video showing how the geolocators are put on the birds.