The world is more saturated than ever with visual images, but we have never properly trained our eyes to look, the Toledo Art Museum’s director told the crowd at the finale of the 2014-15 Jesup Scott Honors College Distinguished Lecture Series.

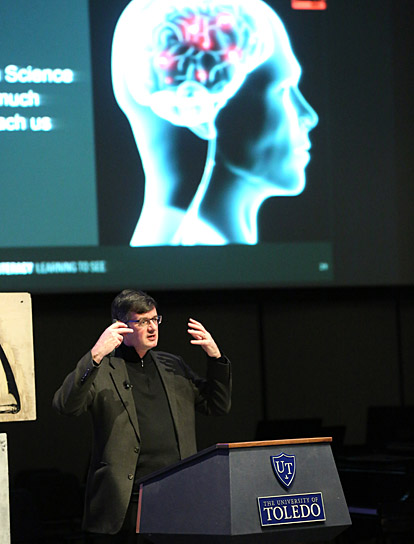

Dr. Brian Kennedy talked about how the brain processes visual information during the Jesup Scott Honors College Distinguished Lecture.

It occurred 5,000 years ago with the first appearance of writing in cuneiform and again 500 years ago with print evolution. Now we are in the midst of a digital revolution and it has happened so fast that it has overwhelmed our education system, he said.

While 90 percent of information from the world is taken in with our eyes, our entire education system is focused on digits and letters rather than scanning to take in all of the visual world around us, not to mention its exclusion of the other senses, Kennedy said.

“If we don’t train ourselves with how to use our senses, we miss out on an awful lot of the world,” he said. “And if we keep on training kids with digits and letters and just computer knowledge and not really load up the curriculum with sensory curriculum — all those things that are about communication, which are about social behavioral skills, all those arts, all those opportunities to engage with each other socially — we will be creating a generation that can’t succeed.”

The process of learning to look starts with looking and making assumptions based on what we’ve seen before. But by taking our time, we can advance the process to be able to see, describe, analyze and interpret what we are looking at, Kennedy said.

Becoming visually literate also requires knowledge of the visual elements of art — line, shape, color, space and texture — and the principles of art — emphasis, balance, harmony, variety, movement, proportion, rhythm and unity.

Kennedy advocated for this training to begin with young children, which is why the museum has programs for babies and toddlers, and to continue throughout formal education and the rest of our lives. He complimented UT’s Lloyd A. Jacobs Interprofessional Immersive Simulation Center for approaching teaching and learning as visual sensory experiences.

“The thing about visual language is that visual language is all over the world. It helps us to see each other and helps us to engage with each other. What it does is it tells us how to approach the world, and we know that the world is actually a series of moments,” Kennedy said.

“Vision creates empathy and the more we know about how to use our eyes, the more empathy we generate and the more tolerant we become.”

Following his talk, Kennedy answered questions about how visual literacy is incorporated into the museum and its exhibits, how culture impacts our sensory experiences, the role of traveling exhibits as a way to expose people to art, and how technology advances will change the art museum experience, among others.