The Power To Do Public Impact Research: Since a harmful algal bloom forced the city of Toledo to issue a “Do Not Drink” water advisory in 2014, UToledo has been working to protect water quality and the health of Lake Erie for the half million people in the region who depend on it for drinking water. This is the third in a five-part series detailing UToledo’s water quality research efforts over the past decade.

The massive tanks might look imposing inside the Defiance Water Treatment Plant, but they’re really not so different than the water pitcher in your refrigerator.

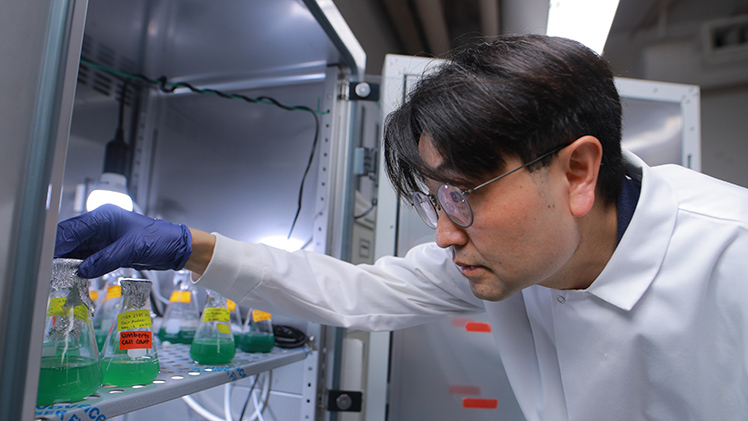

“Think of them like Britas,” suggested Dr. Youngwoo Seo, professor in The University of Toledo’s Departments of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Chemical Engineering. “It’s essentially a carbon filtration system. There is granular activated carbon inside the tanks that facilitates a chemical process known as adsorption, in which contaminants adhere to the carbon.”

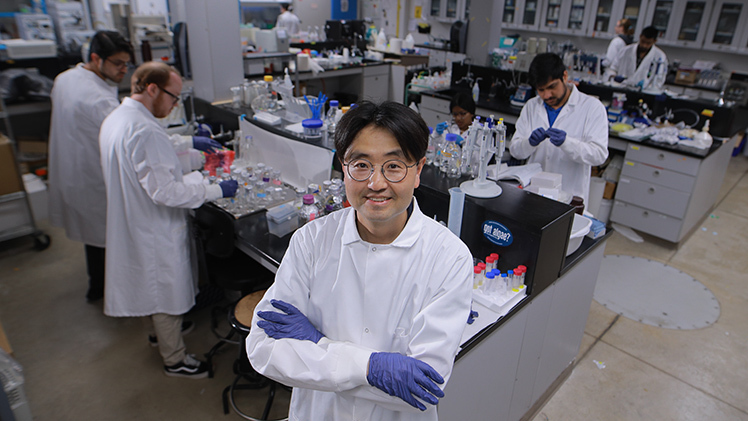

Dr. Youngwoo Seo, professor in The University of Toledo’s Departments of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Chemical Engineering, was among the earliest members of the UToledo Water Task Force that formed in the immediate wake of the water crisis in 2014.

As the price of the granular activated carbon rises, Seo is exploring ways to increase the longevity of the black, crumbly substance that’s key to this tried-and-true method to filter out toxins borne of harmful algal blooms and other contaminants. His research, supported by the Ohio Water Development Authority, is expected to answer specific questions in Bowling Green and Defiance while broadly benefiting water treatment facilities throughout Ohio.

It’s the latest example of the field work typical of Seo, who has been sharing his expertise with water treatment to facilities throughout northwest Ohio since 2014. The Toledo water crisis that cut off potable water to a half-million people catalyzed first a collaboration with operators in Toledo. Supported by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, National Science Foundation, Ohio Water Development Authority and the Ohio Department of Higher Education through its Harmful Algal Bloom Research Initiative, he and his collaborators have since expanded their footprint to Celina, Bowling Green, Defiance and Oregon.

“This isn’t research for the sake of research,” Seo said. “We’re sharing our data and our recommendations with treatment plant operators and managers who are working day and night to keep water clean. I’m happy to have built up such a strong collaboration with these agencies so that I’ve been able to support those who live in the region, including my own family.”

Seo, who joined UToledo’s College of Engineering in 2008, was among the earliest members of the UToledo Water Task Force that formed in the immediate wake of the water crisis in 2014. Like others who joined as chemists, engineers, medical doctors and public health experts, he nimbly pivoted to apply his expertise in biofilms and water treatment processes to the region’s most pressing concern: How to ensure the safety of our drinking water?

It was a particularly basic question in 2014, as demonstrated by the initial round of projects funded by the Harmful Algal Bloom Research Initiative. Seo tackled two projects in that first round, the first investigating which treatment methods could be used to filter water safely, in addition to the carbon filtration that is routinely used alongside other chemical, physical and biological processes, and the second examining whether toxins “stick” to pipes and storage tanks.

(They don’t, at least not in any way that standard chlorination doesn’t clear up.)

Seo has remained committed to understanding and improving how water treatment facilities can best remove toxins in the decade since the crisis, including research into biofilters that was supported by the National Science Foundation in 2016.

Today, Seo heads two projects under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to develop advanced technology for early detection and management of harmful algal blooms and to introduce new monitoring and treatment methods to inland sources and treatment plants.

Biofilters are a water treatment technique that incorporate living material to capture and biologically degrade pollutants. They’re a particular area of interest at UToledo, where researchers including Seo and Dr. Jason Huntley, professor of microbiology and associate dean for faculty affairs and development in the College of Medicine and Life Sciences, continue to investigate the potential of a biofilter based on a naturally occurring bacteria found in Lake Erie.

“Lab experiments have shown that our biofilters quickly remove microcystin at levels far above current exposure guidelines established by the World Health Organization,” said Huntley, who began investigating these naturally occurring bacteria in a first-round project under the Harmful Algal Bloom Research Initiative and more recently received a $1.1 million grant to advance this work through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “They also have the benefit of being very inexpensive to make and maintain. We’re excited to continue developing and improving them for real-world deployment.”

Huntley and his team, with support by UToledo, have patented these biofilters.

Seo’s research with the National Science Foundation supported the city of Toledo’s transition to a new water treatment process that went live in 2021. It implements a biofilter paired with ozonation, an oxidation technique for treating water that can destroy contaminants. Seo worked closely with city officials and a panel of experts to validate the design, and has monitored the system since its installation, sharing data that has allowed operators to optimize the operation.

Today, Seo heads a $1.4 million project under the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to develop advanced technology for early detection and management of harmful algal blooms, and a $1.5 million project under the same agency to introduce new monitoring and treatment methods to inland sources and treatment plants.

Inland water treatment facilities present different challenges than those that pull their raw water supply directly from Lake Erie, Seo said. They tend to rely on reservoirs that stabilize the water supply, but whose stagnant water is prone to algal blooms.

“It’s been extremely helpful to have experts onsite from The University of Toledo,” said Joe Ewers, superintendent of the Defiance Water Treatment Plant. “They understand the issues we’re seeing at a very intricate level and are able to help us address them.”